Pipes that will transport heat through the New Heatway.

Rotterdam is chilly. From November until about the end of April, the

city’s average temperature hovers between 1°C and 5°C (34°F – 41°F). The

problem for many, however, isn’t the cold so much as the darkness, the

wetness and the wind. In fact, most guidebooks recommend that tourists

skip the Netherlands completely until the sun returns in May.

Luckily,

Rotterdam is very good at keeping its residents warm and dry. During

World War II, civil servants at the Municipality of Rotterdam developed

plans for a district heating system. The system, in which multiple

buildings are heated from a central, remote source rather than their own

in-house boilers, was to be implemented during reconstruction of the

areas that had been destroyed during the bombardment. When the war ended

in 1945, Johan Ringers, Minister of Public Works and Reconstruction,

oversaw the rebuilding of the city and the simultaneous placement of a

district heating pipeline. In 1949, Hotel Pax became the first building

to be fully heated by the new system.

District heating is more

energy efficient and produces lower carbon emissions than individual

boilers. Systems vary from country to country, but most produce heat

through cogeneration plants, geothermal heating or nuclear power.

Manhattan, for instance, has a district heating system that’s been

operated by Con Edison, the city’s utility company, since 1882. San

Francisco, Denver and Seattle also use district heating systems, and

Denmark and Germany are increasingly using solar-thermal panels to

source their district heat. But Rotterdam is taking the method a step

further.

With clouds blocking the sun through much of the winter,

solar energy isn’t in abundance here. But water is, and the industrial

activities that take place in the Port of Rotterdam produce an enormous

amount of excess heat. Until 2012, that heat was simply released into

the atmosphere or the Maas River. But today more than 50,000 Rotterdam

households are heated by the port’s residual warmth, with plans to heat

an additional 95,000 by the end of 2014.

New Heatway pipes are installed. The system uses excess energy from the city’s port to heat individual homes.

The process begins at the AVR Waste-to-Energy plant in Rozenburg, a borough of Rotterdam about 20 kilometers west of the CBD

on the southern bank of the Maas River. In addition to household,

industrial and biomass waste, the plant has recently begun to process

imported waste as well. That waste is converted into steam, heat and

electricity through incineration. But it’s also the site of a

groundbreaking project: there, in the biggest waste-slash-power plant in

Europe, residual warmth from surrounding port industries is collected

and diverted into the “New Heatway” (De Nieuwe Warmteweg), a 26-kilometer-long double pipeline running from Rozenburg to the Maasstad Hospital and back, redistributing the excess heat to homes and businesses along the way.

Initiated by Warmtebedrijf Rotterdam,

a public-private initiative, the New Heatway’s initiators and

shareholders include the Province of South Holland, the Municipality of

Rotterdam, WoonBron housing corporation and E.On, the Netherlands’

largest energy provider. Visser & Smit Hanab | Drilling Technologies,

a division of VolkerWessels, are responsible for the New Heatway’s

design, construction and maintenance. Private energy companies then

manage the distribution of the district heating to individual end users.

In Rotterdam, Nuon and E.On are currently providing heat through this

pioneering system.

Back in Rozenburg, water heated through

industrial processes enters the system. At its source, the water is

120°C. Because of the piping system’s heavy insulation, the water only

loses about 2°C by the time it arrives at the distribution centers in

different neighborhoods. From there, the pipelines shrink dramatically,

causing the water to cool much more quickly as it flows from the centers

to individual houses, shops and office buildings, where it generally

arrives at about 70°C. When the water returns to the network and

eventually makes its way back to the AVR plant in the harbor, it can be anywhere between 70°C and 90°C, depending on the time of year.

In

addition to the New Heatway, Eneco is planning to install another

distribution pipeline running north under the Maas River and into

Rotterdam through Vlaardingen and Schiedam. Headquartered in Rotterdam,

Eneco Group is an energy company with about 7,000 employees and a

mission to provide “sustainable energy for everyone.” Construction on

the 16.8 kilometer “Northern Pipeline” (Leiding over Noord) has

already begun – neither Vlaardingen nor Schiedam have local district

heating networks, so it involves a significant amount of pipe-laying

through existing neighborhoods. According to a statement from Eneco,

they have contacted local stakeholders such as developers, housing

corporations, health care facilities and homeowner associations to

evaluate where the system can have the most impact. Eneco also organized

a series of open information meetings to inform local residents and

address public concerns about the project.

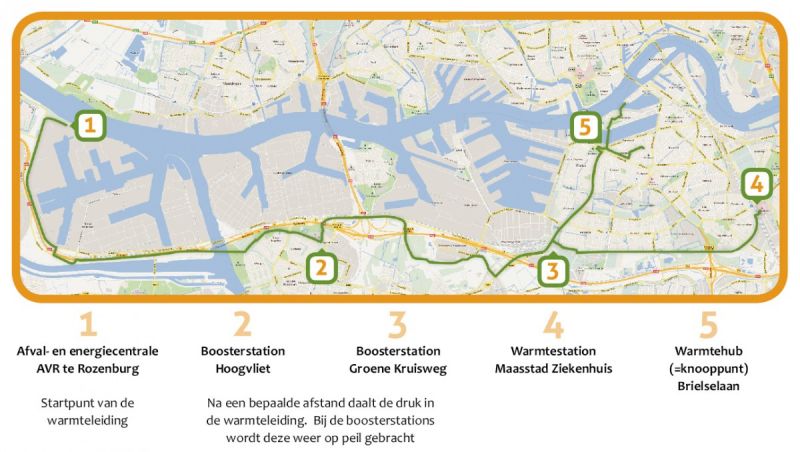

A map of the New Heatway.

A map of the New Heatway.

Beginning in October 2014, Eneco will join the energy providers already buying residual heat from the AVR Energy-from-Waste plant in Rozenburg. “The Leiding over Noord

project will realize environmental benefits for all people living and

working in the Rotterdam area,” says Cor de Ruijter, a press officer for

Eneco. “It will bring a reduction of CO2 emissions by using the heat

from a remote waste-to-energy plant instead of using heat from a

gas-fired power plant in the city. Financially, there will be no change

for the heat consumers. This is an investment of tens of millions of

euros that will give a certain financial return in the long term. But

there will be environmental returns from the first moment heat will go

through the pipe.”

Rotterdam has estimated that the New Heatway

will prevent the release of 70 to 80 kilotons of CO2 annually — roughly

the same emissions produced by 17,000 cars in a year. And Eneco

estimates the reduction results from the Northern Line to be even

higher, at 95 kilotons per year. Together, these two pipelines will have

the net effect of reducing CO2 emissions by about 175 kilotons — more

than some entire countries produce annually. Still, Rotterdam and its

port are responsible for about 16 percent of the CO2 emissions produced

in the Netherlands, so massive emissions reductions are urgently needed.

To put this in perspective, in 2013, Rotterdam produced more CO2

emissions per capita (29.8 tons) than London (9.6) and Shanghai (11.7)

combined. Moreover, the financial benefits for the end consumer are

fairly negligible. Both district heating and natural gas delivered from a

supplier will cost an average household about the same: 1,000 euros per

year.

For Rotterdam, the incentives to reduce carbon emissions

are fairly obvious. And luckily for its citizens, this city is willing

to make big, bold investments to ensure those reductions continue. The

genius of the plan is that, while drastically reducing emissions, it

will keep us warm and dry – unless, of course, we happen to venture

outside between November and April.

No comments:

Post a Comment